Research done in conjunction with Tracy Joji and Michael Whelan.

Abstract

This study investigates how the closure of Distillery Road on the University of Galway campus influences transportation behavior, particularly the shift from car use to active modes such as walking and cycling. Aligned with the University’s goal of achieving Healthy Campus Status and its broader Green-Campus Ireland sustainability commitments, the research examines whether targeted urban design interventions can promote healthier, low-carbon mobility patterns.

By comparing the closed segment of Distillery Road to adjacent roads that remain open to vehicle traffic, the study assesses the impact of infrastructural change on campus mobility. Grounded in public health and sustainability frameworks, the project aims to provide evidence on how reducing car access can support environmental goals, improve quality of life, and foster a more active campus culture. Findings will inform future campus planning decisions and contribute to broader discussions on sustainable transport design in academic environments.

Research Overview and Introduction

As part of the University of Galway’s sustainability efforts, it has committed to achieving the Healthy Campus Status, which emphasizes the importance of creating an environment that enhances the mental, physical, and social well-being of its community. Central to this vision is the promotion of sustainable transportation practices that reduce reliance on private cars while encouraging active transportation methods, such as walking and cycling. With the broader sustainability strategy, the University aims to foster a campus culture that supports both environmental and public health goals while reducing greenhouse gas emissions and improving the quality of life for students and staff.

A key element of this initiative is the examination of how urban design choices — such as road closures — can influence transportation behaviors. This research will investigate the potential impact of such interventions, focusing specifically on the closure of Distillery Road, which runs adjacent to the Kingfisher sports complex, compared with roads on campus that still support car traffic. By evaluating this change, we aim to understand whether the closure of a road like Distillery Road can shift transportation patterns on campus, encouraging greater use of sustainable and active transportation options like walking and cycling while simultaneously discouraging car use.

The central research question guiding this study is: Does blocking car traffic on roads like Distillery Road increase the number of pedestrians and cyclists while dissuading driving?

This question is grounded in the broader context of sustainability and health, as the closure of roads has been shown in other settings to promote active transportation, reduce traffic congestion, and improve community health outcomes. By analyzing how such a change affects transportation choices on the University of Galway campus, we hope to contribute valuable insights into how infrastructure modifications can support the University’s sustainability objectives and its goal of achieving Healthy Campus Status.

Research Statement

With this research project, we aim to evaluate the effects of road closures on campus transportation behaviors, using the closure of Distillery Road at the University of Galway as a case study. We will focus on methods to promote active transport and subsequently reduce car dependency to meet Green-Campus Ireland’s sustainability goals.

This research will explore how changes to campus infrastructure can directly support the University’s Green Campus and sustainability initiatives, particularly in relation to fostering healthier, more active campus communities. By investigating the effects of road closures on transportation choices, we aim to provide evidence that can inform future urban design decisions at the University, as well as offer insights into broader strategies for promoting sustainable transport options in academic and urban settings.

Ultimately, this study seeks to understand the role that road closures can play in reshaping campus mobility and contributing to the University of Galway’s sustainability goals, including improved physical well-being and a reduction in the environmental impact of transportation.

Literature Review

Conceptual Foundation

Promoting sustainable and active transportation practices on college campuses has become a central focus for addressing a broad range of environmental and public health goals. Balsas (2003) highlights the critical role that universities have as a potential proof of concept for sustainable urban design and policy interventions. Balsas emphasizes how transportation infrastructure is intertwined with institutional policies and cultural norms — showing that specific, intentional strategies can alter transportation choices in favor of walking and cycling.

Similarly, Holmes, Huynh and Millard-Ball (2018) explore the benefits of pedestrian-friendly designs within academic environments. Their work highlights the magnitude pedestrianization has in promoting a greater sense of community while improving safety and supporting active transportation use. This literature reinforces the idea that transforming infrastructure, such as closing roads to vehicular traffic, aligns with goals to promote sustainable and healthy lifestyles.

Defining Sustainability

Sustainability, in the context of this research, refers to practices that balance environmental preservation, public health promotion, and social well-being. Beyond its immediate benefits, sustainability plays a critical role in combating climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and fostering resilience within urban spaces. By prioritizing sustainable urban design practices like pedestrianization and active transportation infrastructure, institutions can create long-term solutions that address environmental challenges while enhancing the quality of life for their communities. This dual focus not only aligns with global sustainability targets but also highlights the importance of systemic changes that support ecological, social, and economic resilience in an increasingly urbanized world. Balsas (2003) frames sustainability on college campuses as a multidimensional effort, linking reduced carbon emissions with improved quality of life for campus users. Holmes, Huynh and Millard-Ball (2018) extend this understanding by connecting pedestrianization efforts with reductions in vehicular traffic and enhancements in air quality, contributing to both environmental and social sustainability.

In the context of the University of Galway’s mission to achieve a Healthy Campus Status, sustainability takes on a particularly significant role. By fostering an environment that prioritizes mental and physical well-being, sustainable urban design interventions, such as road closures, directly support this goal. Creating safe and accessible active transportation networks contributes to healthier lifestyles while aligning with organizational priorities. Sustainability, therefore, is not only a global imperative but also a targeted pathway to enhance campus culture and achieve measurable health and environmental outcomes.

By integrating these perspectives, this research defines sustainability as a process of fostering systemic changes that prioritize active transportation, reduce car dependency, and create environments that are both health-promoting and ecologically responsible. This definition provides a foundation for evaluating how urban design choices, such as the closure of Distillery Road, align with sustainability principles.

Foundational Literature

Clifton, Smith, and Rodriguez (2006) explore the relationship between the built environment and physical activity levels, emphasizing the importance of systematic audits to evaluate infrastructure. Their findings suggest that walkable environments are instrumental in encouraging active transportation — and they provide a methodological basis for assessing the impact of changes in campus infrastructure. All of this aligns with the current research goals, both of which seek to understand how urban design influences transportation behaviors.

In addition, dell’Olio et al. (2018) focus on examining methodologies that evaluate transportation preferences. Their work provides insights into what influences individual transportation decisions, employing both revealed and stated preference survey techniques — the study provides insights into the factors influencing transportation decisions. dell’Olio’s work offers a rich methodological framework that sheds light on how road closures may impact modal shifts toward walking and cycling on a college campus.

Woodcock et al. (2009) provides further foundational insight by highlighting the intersection of transportation planning and public health. The study demonstrates that strategies reducing greenhouse gas emissions, such as promoting walking and cycling over car usage, yield significant public health benefits; chief among them, reduced mortality and morbidity from air pollution and increased physical activity. Their work supports the argument that strategies like closing roads are environmentally beneficial — and lead to healthier communities. Their findings support the thesis that sustainable transportation initiatives are essential not only to climate action but public health objectives as well.

Methodological Foundations

The methodologies outlined in the literature serve as critical tools for designing and executing this research. Clifton et al.’s (2006) work on physical audits informs the approach to assessing how infrastructure changes affect walking and cycling behaviors. These audits can provide objective, quantifiable data on the usability and appeal of pedestrian and cycling paths, particularly following interventions like road closures.

dell’Olio et al.’s (2018) application of discrete choice models and preference surveys highlights the value of combining quantitative and qualitative data to understand user behaviors and preferences. By using similar methods, this research can capture a rich data set, including observed changes in transportation patterns and the underlying motivations driving these shifts. The goal is to create a replicable and comprehensive toolkit to evaluate the impact of closing roads like Distillery Road on sustainable transportation practices at the University of Galway.

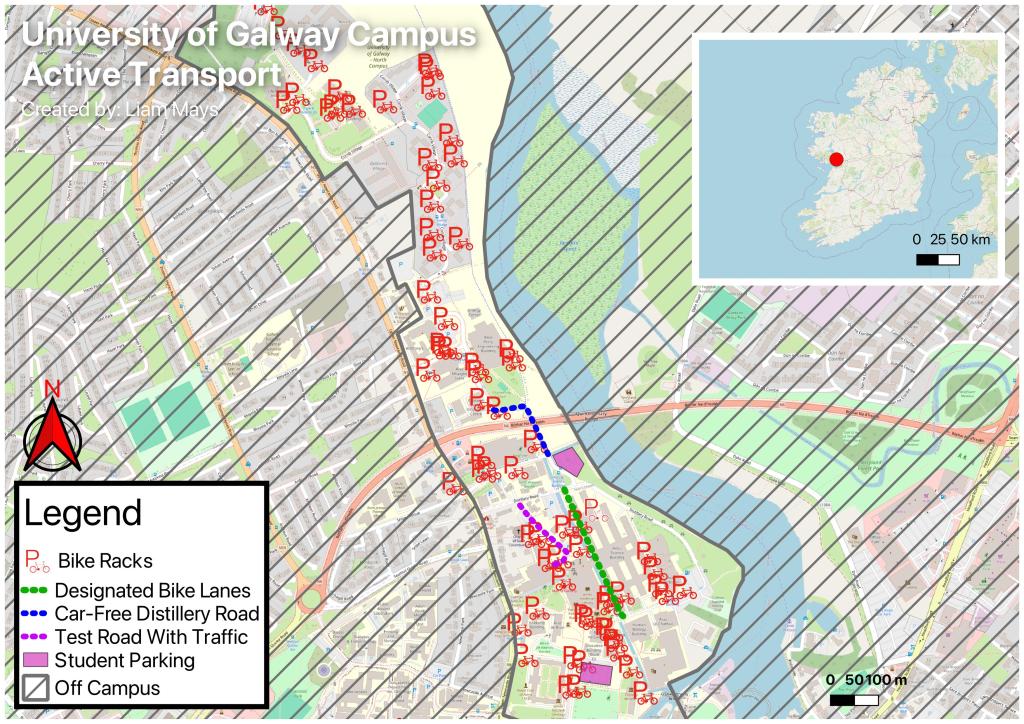

Site Description

This research will focus on a stretch of Distillery Road on the University of Galway campus, beginning near the southeast corner of the Kingfisher Fitness Club and ending at the Science and Engineering Technology Building. This stretch of road is shut off to cars — only allowing pedestrians, cyclists and buses. It essentially acts as an active transport throughway from north campus — which includes the bulk of student housing — down to south campus. Raising bollards ensure access to buses and prevent car traffic.

Prior to 2023, this stretch was open to car traffic and bottlenecked pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles. Under the N6 national primary road, the sidewalk narrowed leaving little space isolating walkers from vehicle traffic — creating a potentially hazardous environment.

Additionally, this research will examine a section of road that spans from Distillery Road to the Arts Millennium Building, which remains open to car traffic. This section receives significant foot and cyclist traffic conflicting with vehicles — especially in the evenings. Comparing these two sections provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the impact of road closures on transportation behaviors within the same campus context. By contrasting the pedestrianized section of Distillery Road with the adjoining car-accessible area, the research can illuminate how such interventions influence mobility choices, safety, and the broader adoption of sustainable transportation practices.

Areas around the central points of this research can give more context to better understand campus transportation patterns. For instance, there is only one identifiable bike lane on the University of Galway campus, which means cyclists are frequently sharing space with either pedestrians or vehicles, which creates safety concerns.

Additionally, there are many prominent roads running through campus that accommodate a consistent flow of cars, limiting the opportunity for safer and more convenient active transportation use. The campus is also surrounded by roads with high speed limits that experience heavy car traffic, like the N6 national primary road.

The surrounding external conditions, from limited bike lanes to heavily trafficked roads nearby, could alter transportation choices, causing residents to favor cars over active transportation options. People may perceive cars as safer, more convenient choices, especially during inclement weather. These factors underscore how important this research is, as it examines the impact of road closures within a difficult environment where a dependency on cars is high and active transportation infrastructure is limited. Interpreting how road closures can thwart these issues will contribute to a wider effort of the adoption of sustainable transportation use on campus.

Methodologies

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, integrating both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis to comprehensively evaluate the impact of closing campus roads on transportation behaviors. The backbone of the data collection will be a combination of revealed preference (RP) and stated preference (SP) survey methodologies, supplemented by observational audits using the PEDS (Pedestrian Environment Data Scan) system. These methods will provide insights into both existing patterns and potential future preferences, ensuring a robust understanding of the effects of road closure.

Quantitative data will be collected through:

Revealed Preference Surveys: These will capture current transportation behaviors, including mode choice, frequency of trips, and patterns of use for both the pedestrianized and car-accessible sections of road within the scope of this research (dell’Olio et al., 2018). Data types include trip counts, mode shares (walking, cycling, bus, car), and travel times.

PEDS Audits: The PEDS system will be used to evaluate the physical environment of both road sections. Metrics will include sidewalk width, path quality, availability of bike lanes, and pedestrian safety features (Clifton, Smith and Rodriguez, 2006).

Quantitative data will undergo statistical analysis using software such as R. Descriptive statistics will summarize patterns, while inferential tests like ANOVA will compare the pedestrianized and non-pedestrianized sections. An employment of space syntax analysis may be used to examine how closing a road to car traffic influences spatial accessibility and movement patterns. Additionally, regression analysis may be used to identify correlations between the intervention and changes in active transport user numbers, controlling for relevant variables (Hacar, Gülgen and Bilgi, 2020).

Qualitative data will complement the quantitative findings and provide context to user experiences and preferences.

Stated Preference Surveys: These surveys will ask participants about their hypothetical transportation choices under varying scenarios, for example, expanded pedestrian zones, additional cycling infrastructure like bike racks and paths, and fewer roads with car traffic on and around campus. Open-ended responses will provide insights into perceived barriers and enablers of sustainable transportation (dell’Olio et al., 2018).

The qualitative data will undergo thematic and content analysis using the following coding themes:

- Safety

- Keywords: “unsafe,” “dangerous,” “accidents,” “visibility,” “traffic,” “speed limit.”

- Convenience

- Keywords: “accessibility,” “time-saving,” “easy to navigate,” “proximity.”

- Sustainability

- Keywords: “eco-friendly,” “carbon footprint,” “environmental impact.”

- Infrastructure

- Keywords: “sidewalks,” “bike lanes,” “crosswalks,” “bike racks.”

- Behavioral Shifts

- Keywords: “change,” “adaptation,” “new habits,” “culture.”

The mixed-methods approach ensures that quantitative findings like changes in trip counts and mode shares are enriched by qualitative insights like user attitudes and experiences. This data will provide a holistic understanding of the current and potential impact of closing campus roads to car traffic on transportation behaviors and sustainability goals.

Research Justification

Research has shown that restricting cars from roads not only reduces the amount of drivers and increases active transportation users (Nieuwenhuijsen and Khreis, 2016) but has a myriad of other benefits as well. This infrastructural change, coupled with policy changes to increase the appeal of active transport, has served as a catalyst for healthier living in cities across the world. From improved air quality due to less greenhouse gas emissions from cars to reduced on-road accidents and injuries to the inherent benefit of physical activity being a standard mode of transportation (Woodcock et al., 2009).

There is an extensive amount of international research about the benefits of pedestrianizing streets and subsequently reducing car dependence, but there is a gap in understanding how these infrastructural changes might function within the specific context of Ireland. There are unique circumstances in the nation like high car ownership rates accompanied by a relatively car-centric culture, which might present distinct roadblocks to the popular use of active transportation methods such as walking and cycling. Ireland’s weather, with frequent rain and extreme winds, may also deter some from outdoor activities and the use of sustainable modes of transportation for commuting purposes. These factors make local research necessary to evaluate how pedestrianization, like the closure of Distillery Road, can hurdle these barriers. Discerning the impactfulness of these infrastructural interventions within the context of Ireland is vital for creating specific strategies that are both culturally and environmentally appropriate, which can pave the way for wider implementation in similar areas.

Successfully dissuading commuting by car and persuading the use of active transportation via infrastructural changes like the pedestrianization of roads would not only significantly factor into achieving the University of Galway’s goal of reaching a Healthy Campus Status, but it would also embed sustainability into the culture of the university.

Likely outcomes of this research include a clearer understanding of how pedestrianized zones affect transportation patterns, safety, and the adoption of active transportation in a campus setting. This study could reveal specific design and policy elements that are critical for encouraging walking and cycling, even in the face of adverse weather or ingrained car dependency. Additionally, it may provide a model for implementing similar interventions in other Irish universities or urban settings.

Possible further pathways include exploring the long-term effects of campus pedestrianization on community well-being, including mental and physical health outcomes, or examining how similar interventions could be expanded to adjacent urban areas to encourage students and staff living further from campus to use active transportation. Additional research could examine if complementary infrastructure — including covered walkways, more bike lanes, higher parking fares, and improved public transportation links —can enhance the effectiveness of pedestrianized streets.

In addition, this research could provide complementary opportunities to engage with stakeholders, such as students, staff, and local policymakers, to co-develop recommendations for sustainable and health-promoting campus designs. It also enriches the University of Galway’s broader sustainability initiatives by providing evidence-based insights that support its Healthy Campus Status goal.

By focusing on the closure of Distillery Road compared with the road connecting Distillery Road to the Arts Millenium Building, this work contributes to quantifying progress toward achieving the Healthy Campus Status. Specifically, it assesses how changes in the built environment influence the mental, physical, and social well-being of the campus community. Through measurable outcomes like increased use of active transportation, reduced car usage, and improved safety, this research directly supports the university’s mission to create a learning environment and culture that is mindful of and enhances holistic well-being.

Bibliography

Balsas, C.J.L. (2003) ‘Sustainable transportation planning on college campuses,’ Transport Policy, 10(1), pp. 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-070x(02)00028-8.

Clifton, K.J., Smith, A.D.L. and Rodriguez, D. (2006) ‘The development and testing of an audit for the pedestrian environment,’ Landscape and Urban Planning, 80(1–2), pp. 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2006.06.008.

dell’Olio, L. et al. (2018) ‘A methodology based on parking policy to promote sustainable mobility in college campuses,’ Transport Policy, 80, pp. 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2018.03.012.

Hacar, Ö., Gülgen, F. and Bilgi, S. (2020) ‘Evaluation of the Space Syntax Measures Affecting Pedestrian Density through Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis,’ ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(10), p. 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9100589.

Holmes, S., Huynh, R. and Millard-Ball, A. (2018) ‘Pedestrian planning on college

campuses,’ Planning for Higher Education, pp. 1–16. https://www.proquest.com/openview/ae876fb17adec4ef18e7614a6d33ab43/.

Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. and Khreis, H. (2016) ‘Car free cities: Pathway to healthy urban living,’ Environment International, 94, pp. 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.05.032.

Woodcock, J. et al. (2009) ‘Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: urban land transport,’ The Lancet, 374(9705), pp. 1930–1943. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61714-1.

Leave a comment